A study in the journal, JAMA Neurology suggests that controlling or preventing risk factors such as hypertension earlier in life may limit or delay the brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease and other age-related neurological deterioration.

Dr. Karen Rodrigue, assistant professor in the UT Dallas Center for Vital Longevity (CVL), was lead author on a study that looked at whether people with both hypertension and a common gene associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease (the APOE-4 gene carried by about 20 percent of the population) had more buildup of the brain plaque (amyloid protein) associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Many scientists believe the amyloid plaque is the first symptom of Alzheimer’s disease and shows up a decade or more before Alzheimer’s symptoms of memory impairment and other cognitive difficulties begin.

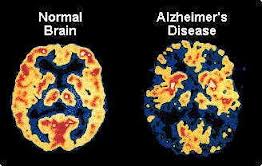

Until recently, amyloid plaque could only be seen at autopsy, but new brain scanning techniques allow scientists to see the amyloid plaque in living brains of healthy adults. Findings from both autopsy and amyloid brain scans show that at least 20 percent of normal older adults carry elevated levels of amyloid, a substance made up mostly of protein and deposited in organs and tissues.

New research showed unmedicated hypertensive adults with the APOE-e4 gene, a risk factor for Alzheimer’s, showed much higher levels of amyloid plaques than those taking medication for hypertension and with the same genetic risk factors. The image is a plastinated brain of an Alzheimer’s patient.

“I became interested in whether hypertension was related to increased risk of amyloid plaques in the brains of otherwise healthy people,” Rodrigue said. “Identifying the most significant risk factors for amyloid deposition in seemingly healthy adults will be critical in advancing medical efforts aimed at prevention and early detection.”

Based on evidence that hypertension was associated with Alzheimer’s disease, Rodrigue suspected that the double-whammy of hypertension and presence of the APOE-e4 gene might lead to particularly high levels of amyloid plaque in healthy adults.

Rodrigue’s research was part of the Dallas Lifespan Brain Study, a comprehensive study of the aging brain in a large group of adults of all ages funded by the National Institute on Aging. As part of this study, the research team recruited 147 participants (ages 30-89) to undergo cognitive testing, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and PET imaging, using Amyvid, a compound that when injected travels to the brain and binds with amyloid proteins, allowing the scientists to visualize the amount of amyloid plaque. Blood pressure was measured at each visit.

Rodrigue classified participants in the study as hypertensive if they reported a current physician diagnosis of hypertension or if their blood pressure exceeded the established criteria for diagnosis. The participants were further divided between individuals who were taking anti-hypertensive medications and those who were not medicated, but showed blood pressure elevations consistent with a diagnosis of hypertension. Finally, study subjects were classified in the genetic risk group if they were in the 20 percent of adults who had one or two copies of an APOE ε4 allele, a genetic variation linked to dementia.

The most striking result of the study was that unmedicated hypertensive adults who also carried a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, showed much higher amyloid levels than all other groups. Adults taking hypertensive medications, even those with genetic risk, had levels of amyloid plaque equivalent to participants without hypertension or genetic risk.

The study suggests that controlling hypertension may significantly decrease the risk of developing amyloid deposits, even in those with genetic risk, in healthy middle-aged and older adults. Rodrigue noted that long-term studies of many people were needed to be certain that it was the use of hypertensive medications that was causal of the decreased amyloid deposits. Nevertheless, this early finding provides a window into the potential benefits of controlling hypertension that goes beyond decreasing risk of strokes and other cardiovascular complications.

Scientists cannot fully explain the neural mechanisms underlying the effect of hypertension and APOE ε4 on amyloid accumulation. But earlier research in animal models showed that chronic hypertension may enable easier penetration of the blood-brain barrier, resulting in more amyloid deposition.

The recent study is significant because it focuses on a group of healthy and cognitively normal middle-aged and older adults, which enables the examination of risk factors and amyloid burden before the development of preclinical dementia. The team plans for long-term longitudinal follow-up with participants to determine which proportion of the subjects eventually develop the disease.

Notes about this Alzheimer’s disease research

The study’s coauthors included Dr. Denise Park, director of the Dallas Lifespan Brain Study, and Dr. Kristen Kennedy and doctoral student Jennifer Rieck, all from The University of Texas at Dallas. The team also included Dr. Michael Devous and Dr. Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, scientists from UT Southwestern Medical Center and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. In addition to the National Institute on Aging, the Alzheimer’s Association provided funds for the study. Avid Radiopharmaceutical provided doses of Amyvid that allowed the researchers to image the amyloid plaque with a PET scan.

Contact: Emily Martinez – University of Texas at Dallas

Source: University of Texas at Dallas press release

Image Source: The Alzheimer’s disease brain image is available in the public domain.

Original Research: Abstract for “Risk Factors for β-Amyloid Deposition in Healthy Aging Vascular and Genetic Effects” by Karen M. Rodrigue, PhD; Jennifer R. Rieck, MS; Kristen M. Kennedy, PhD; Michael D. Devous, PhD; Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, PhD and Denise C. Park, PhD in JAMA Neurology. Published online March 18 2013 doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.1342