Nocturnal sleep enhances working memory training in patients with Parkinson’s disease but not in those with Lewy body dementia, results from a novel study demonstrated.

The observed performance improvements “are striking because working memory capacity is degraded in patients with Parkinson’s disease, and cognitive impairments in this population may lead to impaired workplace functioning, worsened quality of life, increased risk for maintaining independent living and increased burden to caregivers,” researchers led by Michael K. Scullin, Ph.D., wrote in a study published online August 20, 2012 in Brain.

“Training working memory after first correcting existing sleep disturbances may help alleviate some of the non-motor burdens associated with Parkinson’s disease,” the investigators in this study suggested.

“Training working memory after first correcting existing sleep disturbances may help alleviate some of the non-motor burdens associated with Parkinson’s disease,” they suggested.

Dr. Scullin, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of neurology at Emory University, Atlanta, and his associates set out to investigate whether patients with Parkinson’s disease can improve their working memory performance and, if so, whether slow-wave sleep or another sleep-dependent variable is associated with such improvements.

They enrolled 53 patients with Parkinson’s disease and 10 patients who had dementia with Lewy bodies. All patients spent 48 hours in a laboratory setting where they underwent two nights of polysomnography and eight digit span tests. The timing of assessments was tailored to each patient depending on their typical sleep and wake times (Brain 2012 Aug. 20 [doi:10.1093/brain/aws192]).

On average, Parkinson’s patients were younger than patients who had dementia with Lewy bodies (a mean age of 64 vs. 70 years, respectively). Of the 53 Parkinson’s patients, 42 were taking one or more dopaminergic agents while 11 were not. After sleeping, Parkinson’s patients showed a significant improvement in the digit span backward measure from the mean of tests on day 1 to the mean of tests on day 2, particularly between test four on day 1 to test five on day 2 (P less than .001) but not in the digit span forward measure. The improvement corresponded to nearly a one-digit improvement in the length of the digit span remembered.

In the digit span test, the investigator reads a string of digits aloud and the patient is instructed to immediately recall those digits either in the forward position, which is a measure of short-term memory/attention, or in the backward position, which is a measure of working memory.

On the other hand, patients who had dementia with Lewy bodies showed no significant improvement in the digit span backward measure but showed a significant decline in the digit span forward measure (P less than .05).

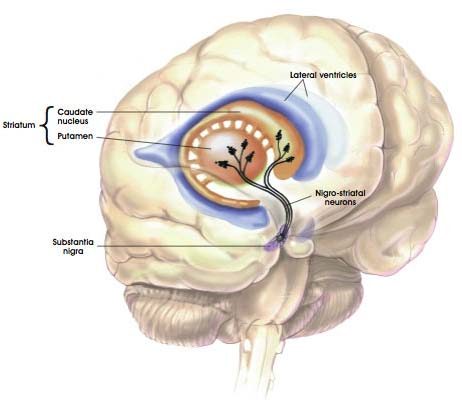

Among Parkinson’s patients, those who were taking dopaminergic medication had significant improvements on the digit span backward measure between day 1 and day 2 (P less than .001) but those who were not taking dopaminergic medication did not (P = .19).

“This pattern is striking, considering that patients taking dopaminergic medication had longer disease duration than those not taking dopaminergic medication,” the researchers noted. Such digit span backward improvements “appear to be dependent on processes that occur during nocturnal sleep rather than … on time of day or practice.”

They arrived at this conclusion by conducting a hierarchical analysis of three potential explanations for the digit span backward improvements observed over the 2-day period: the presence of dopaminergic medication, slow-wave sleep, and nocturnal oxygen saturation. The strongest predictor of digit span backward improvement was nocturnal slow-wave sleep during the training phase.

“An implication of the associations between sleep-dependent processes and working memory performance improvements is that behavioral studies of working memory need to assess the contributions of sleep,” the researchers wrote. “For example, training studies might pre-screen potential participants using overnight polysomnography and/or ambulatory pulse oximetry. A related approach is to continue to monitor sleep architecture and breathing in sleep during the training phase. Doing so allows for the examination of how fluctuations in sleep processes predict working memory capacity improvements.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Scullin also received funding from a Cottrell Fellowship from Emory University.