A report published in the August issue of Archives of General Psychiatry, a JAMA Network publication, has found that patients with hoarding disorder had abnormal activity in regions of the brain that was stimulus dependent when the person had to decide what to do with objects that either belonged to them, or someone else.

Hoarding disorder (HD) is when a person excessively collects objects and is unable to throw them away even though these objects might be useless or invaluable. The person usually has poor insight, avoids any decisions regarding their possessions, and is very attached to all of his/her belongings.

The disorder can be dangerous and cause many health hazards. For example, a clutter of useless objects can put the person at risk for a fire, falling, or even poor sanitation. It can also prevent typical uses of space, like not being able to cook, clean, or sleep because the person runs out of room for their objects and needs those areas.

The popular show “Hoarders” on A&E has shown people struggling with this disorder and unable to toss anything away, resulting in a house full of clutter. This problem has been linked with other psychological problems, like difficulty with attention, and is also associated with perfectionism (the person is afraid to throw something away that they shouldn’t).

In order to measure neural activity when people made decisions about whether to keep or throw away objects, David F. Tolin, Ph.D., of the Institute of Living, Hartford, Connecticut, and team used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

The study consisted of 107 adults from a private, not-for-profit hospital. Among those patients, 43 had HD, 31 had obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and 33 were healthy individuals. In each of these groups, the researchers analyzed neural activity. Paper items, like junk mail and newspapers, that either belonged to the participants or did not, were used as the objects.

Results showed:

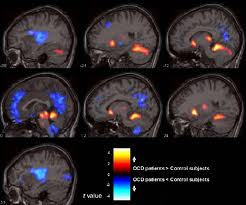

Patients with HD had abnormal activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and insula, compared with participants who had OCD and the healthy individuals.

Patients with HD had relatively lower activity in those brain regions when deciding what to do with objects that did not belong to them.

These brain regions showed “excessive functional magnetic resonance imaging signals” compared with the other groups when they had to decide about objects that belonged to them.

The researchers explained: “The present findings of ACC and insula abnormality comport with emerging models of HD that emphasize problems in decision-making processes that contribute to patients’ difficulty discarding items.”

Results also revealed that the group of patients with hoarding disorder decided to discard a significantly fewer amount of participant’s possessions (PPs) than the other two groups.

The authors concluded:

“The apparent biphasic pattern (i.e., hypo function to Eps [experimenter’s possessions] but hyper function to PPs [participant’s possessions]) of ACC and insula activity in patients with HD merits further study.”