Few patients with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease appear to receive a correct diagnosis when first assessed by a physician, and many receive multiple misdiagnoses until finally being correctly diagnosed two-thirds of the way through the course of the fatal disease.

In a case series of 97 patients with the disease, only 17 (18%) were correctly diagnosed when first assessed by a physician. The average patient received four misdiagnoses and endured 8 months of evaluation before Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) was finally identified, according to the report, published online Sept. 24 in Archives of Neurology.

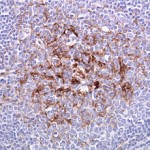

CJD, which is almost always fatal within 1 year, can be difficult to diagnose because early symptoms and signs are so variable and are easily mistaken for those of other neurodegenerative conditions. But the “lack of recognition of this condition in the medical community” is also to blame, especially the fact that many physicians aren’t aware that diffusion-weighted MRI has a sensitivity of 91%-96% and a specificity of 91%-95% in differentiating CJD from other brain disorders, said Dr. Ross W. Paterson of the department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, and his associates.

The investigators described their study as the first large-scale examination “of pathologically proven cases of spontaneous CJD that retrospectively determines what misdiagnoses are made in the work-up of [the disease], who makes these misdiagnoses, and how long it takes to reach the correct diagnosis.”

A total of 76% of the patients in this study were first assessed by internists (40%) or neurologists (36%), comprising “the vast majority of the physicians making the misdiagnoses,” the researchers noted. In 73% of the cases, a neurologist was the first specialist to perform an assessment.

Dr. Paterson and his colleagues studied the issue because they had observed that many families of patients referred to the UCSF Memory and Aging Center complained about the typical delay in diagnosis. Their loved ones had been subjected to extensive and costly evaluations for other conditions, and the families had failed to be protected from a transmissible prion disease. And the delay had deflected both patients and families from focusing on palliative care and end of life planning for this incurable disease.

The 40 female and 57 male subjects were treated at UCSF in 2001-2007. Their ages ranged from 26 to 83 years, with a mean age of 62 years.

Before being correctly diagnosed, the study subjects had received 373 misdiagnoses, with an average of approximately 4 per patient. Of 16 possible categories of disease under which they were misdiagnosed, the most frequent categories were neurodegenerative, autoimmune, infectious, toxic/metabolic, and “unknown dementia.”

The most common individual misdiagnosis was viral encephalitis, most likely because of “the multifocality, acuity, and rapidity of symptoms seen in CJD,” Dr. Paterson and his associates said (Arch. Neurol. 2012 Sept. 24 [doi:10.1001/2013.jamaneurol.79]).

In addition to internists and neurologists, a smattering of other physicians also misdiagnosed CJD when patients first presented with symptoms. These included six ophthalmologists, four psychiatrists, four cardiologists, two otolaryngologists, two orthopedists, and one neuro-oncologist.

The results of this study indicate that sporadic CJD should be considered “in any patient with a rapidly progressive dementia who has been given multiple potential diagnoses,” such as those with neurodegenerative, autoimmune, infectious, or toxic/metabolic etiologies, the investigators wrote. And “if evidence to support a diagnosis of viral encephalitis, paraneoplastic disorder, depression, peripheral vertigo, Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, dementia (nonspecified), CNS vasculitis, peripheral neuropathy, or Hashimoto encephalopathy is lacking, then the clinician should think about requesting an MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging/apparent diffusion coefficient sequences to look for changes associated with sporadic CJD,” they noted.

Moreover, since many radiology reports miss the pathognomonic MRI findings of CJD, “it is critical that physicians be aware of MRI findings in prion disease and read their patients’ MRIs [themselves],” Dr. Paterson and his associates added.

Although this study targeted patients with CJD, misdiagnosing CJD in a patient who has a different etiology for their rapidly progressive dementia is just as harmful, because many of these other dementias are treatable. A recent study demonstrated that 32% of patients referred to the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center for autopsy because of suspected CJD were actually found to have other diagnoses. A total of 7% had had a treatable etiology but went untreated because they were mistakenly diagnosed as having CJD, Dr. Paterson and his associates noted.

It is also incumbent on physicians to make the correct diagnosis so that transmission of this prion disease is avoided – particularly transmission via contaminated surgical equipment or medical procedures, they added.

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Michael J. Homer Family Fund, the National Center for Research Resources, and the John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation. One of Dr. Paterson’s associates reported ties to TauRx Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Siemens Molecular Imaging, and Allon Therapeutics.